Pulmonologists' experiences with palliative sedation for terminally ill patients

Main findings

The doctors reported that palliative sedation for pulmonary patients was mainly administered following interdisciplinary discussions and in accordance with applicable guidelines.

Palliative sedation was administered to pulmonary patients in various diagnostic groups.

The pulmonologists experienced numerous ethical dilemmas in relation to palliative sedation but also felt supported and reassured. Not all the practitioners performing the sedation were familiar with the Norwegian Medical Association's guidelines on palliative sedation, and some considered them unclear.

Palliative sedation has been criticised for being unethical and difficult to distinguish from euthanasia (1). Euthanasia is prohibited under Norwegian law and violates the Code of Ethics for Doctors (2, 3). The so-called Bærum case (4, 5) prompted the Norwegian Medical Association to devise ethical guidelines in 2000, which were then revised in 2014 (1). In these guidelines, palliative sedation is defined as medication-induced reduction of consciousness to alleviate suffering that cannot be relieved in any other way (6). It is an option that is only used in exceptional circumstances, specifically for patients experiencing intolerable suffering at the end of their life. The aim is to reduce the level of consciousness so that the suffering is not experienced in a conscious state.

'Intolerable suffering' is not further defined. Prior to administering sedation, a comprehensive decision-making process involving interdisciplinary palliative care expertise must take place, and it should only be considered for patients with a short life expectancy (6). International guidelines indicate that sedation may be used for patients with refractory psychological symptoms in exceptional cases, and separate conditions are outlined for cases of existential distress (7, 8). There has also been discussion on what is covered in the definition of palliative sedation, which does not include, inter alia, drowsiness caused by symptomatic treatment.

Palliative sedation studies have primarily been conducted with cancer patients (9), but other patient groups may also be indicated. Patients with incurable pulmonary conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and pulmonary fibrosis, as well as neurodegenerative diseases, can experience severe dyspnoea and mucoid impaction in the final phase. Many would characterise this as 'unbearable'' and the symptoms cannot always be alleviated with standard treatments. The use of palliative sedation varies by country and medical specialty, depending on the prognosis and primary symptoms (10). Decision-making processes, administration and patient life expectancy also differ (11). A need has been identified to improve the quality of the decision-making (12), and an EU project has revised the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework for the use of sedation in palliative care (13,14). The framework indicates that palliative sedation may be appropriate when life-sustaining treatment is discontinued and refractory suffering is anticipated, such as the sensation of suffocation following withdrawal of non-invasive ventilation and high-flow oxygen therapy.

Through our own clinical experience (Margrethe Aase Schaufel and Katrin Ruth Sigurdardottir) and enquiries to clinical ethics committees (Reidun Førde and Ingrid Miljeteig), we have identified a need for more knowledge on the application of the guidelines. As far as we are aware, no studies have been conducted on palliative sedation in a pulmonary medicine context in Norway. The aim of this study is therefore to investigate pulmonologists' familiarity with the guidelines in Norway, along with their experiences with and application of these.

Material and method

Before the Norwegian Association for Pulmonary Medicine's autumn meeting in 2022, an electronic questionnaire was sent to all members (529 doctors). A reminder was sent to all of these doctors after the autumn meeting. The questionnaire was devised and piloted in a collaboration between nine specialists in pulmonary medicine, ethics and palliative care, and was inspired by complex case reports and problems that arise where these fields intersect. It was not necessary to seek prior approval from an ethics committee or data protection officers as the study was outside the scope of Norway's Health Research Act and did not entail the collection of personal information or IP addresses.

The questionnaire (see the appendix) consisted of multiple-choice questions and allowed for free-text comments on the decision-making process for palliative sedation, ethical challenges, factors that fostered reassurance and uncertainty, and suggestions for the guidelines.

The responses were analysed using descriptive statistics, and the free-text comments were analysed through systematic text condensation (15). The latter is a cross-case thematic analysis method consisting of four steps: 1) reading all the material to form an overall impression; 2) identifying meaning units that represent different aspects of experiences, and coding these; 3) condensing and extracting the content from the individual meaning units; and 4) summarising and generalising descriptions and concepts.

Results

A total of 50 doctors responded to the questionnaire (9.5 % response rate), of which 38 were specialists and 10 were specialty registrars (two did not indicate their specialist status). The age distribution was even, with 29 working at local hospitals and 17 at university hospitals. Two were specialists in private practice and two did not specify their place of work.

A total of 22 respondents were familiar with the Norwegian Medical Association's guidelines for palliative sedation, while eight were unsure and the rest were not aware of them. In response to questions about whether the guidelines were useful in clinical practice, 7 out of 22 felt they were clear and served as an effective support tool in the decision-making. The remainder either indicated that the guidelines could have been clearer, or that they were unclear, or that they were unsure of their usefulness.

Thirty-seven respondents reported that palliative sedation was practised at their place of work, 11 indicated that it was not, and the remaining two were not sure. There was considerable variation in the frequency of palliative sedation (see Table 1). Those who reported it to be a weekly occurrence at their workplace were either unsure about or unfamiliar with the Norwegian Medical Association's guidelines. Twenty-five of the participants had been involved in administering palliative sedation at least once. Nineteen had experienced ethical challenges related to palliative sedation.

Table 1

The number of doctors who reported that palliative sedation was performed at their workplace, and how often. Based on the responses of 50 doctors in an electronic questionnaire sent to all members of the Norwegian Association for Pulmonary Medicine in 2022.

| Palliative sedation is practised in my department | n |

|---|---|

| No | 11 |

| Yes, less than once a year | 12 |

| Yes, a few times a year | 9 |

| Yes, every month | 11 |

| Yes, every week | 5 |

| Unsure | 2 |

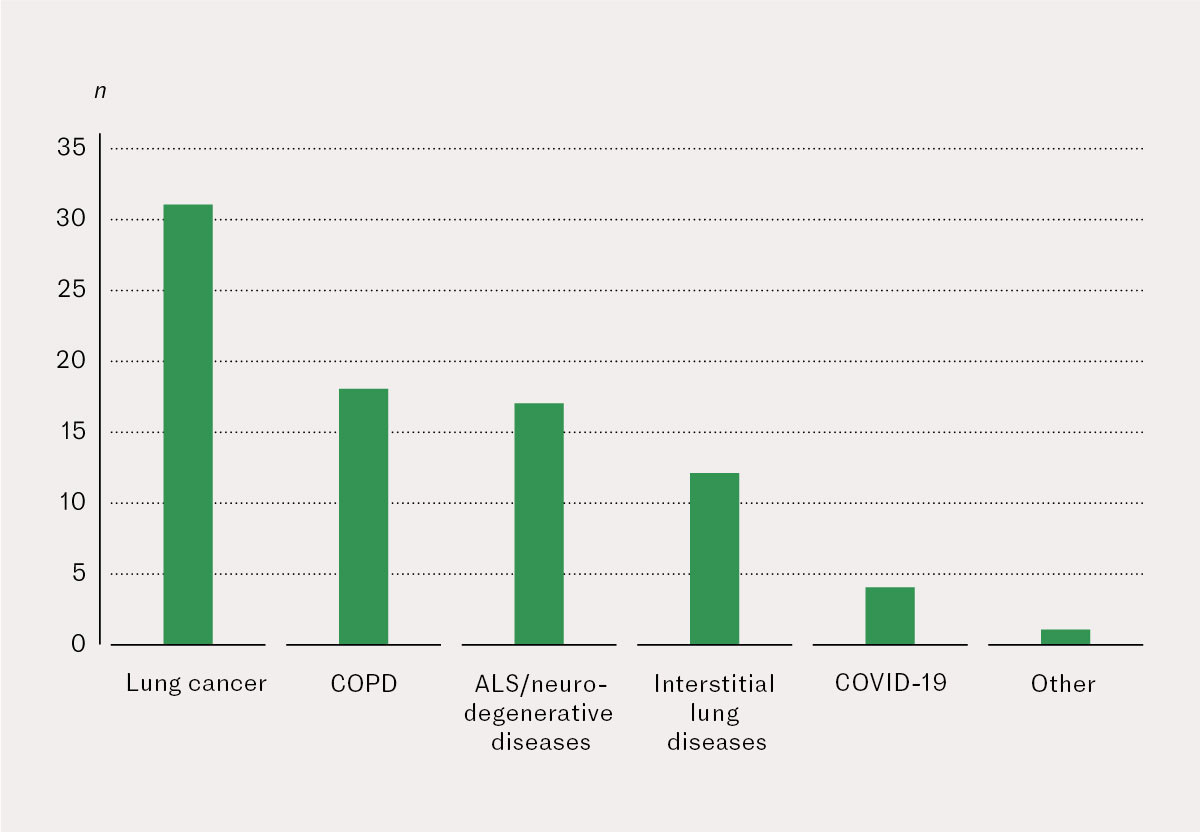

Palliative sedation was used for various diseases (see Figure 1). The most frequently mentioned group was patients with lung cancer, followed by COPD and ALS/neurodegenerative diseases.

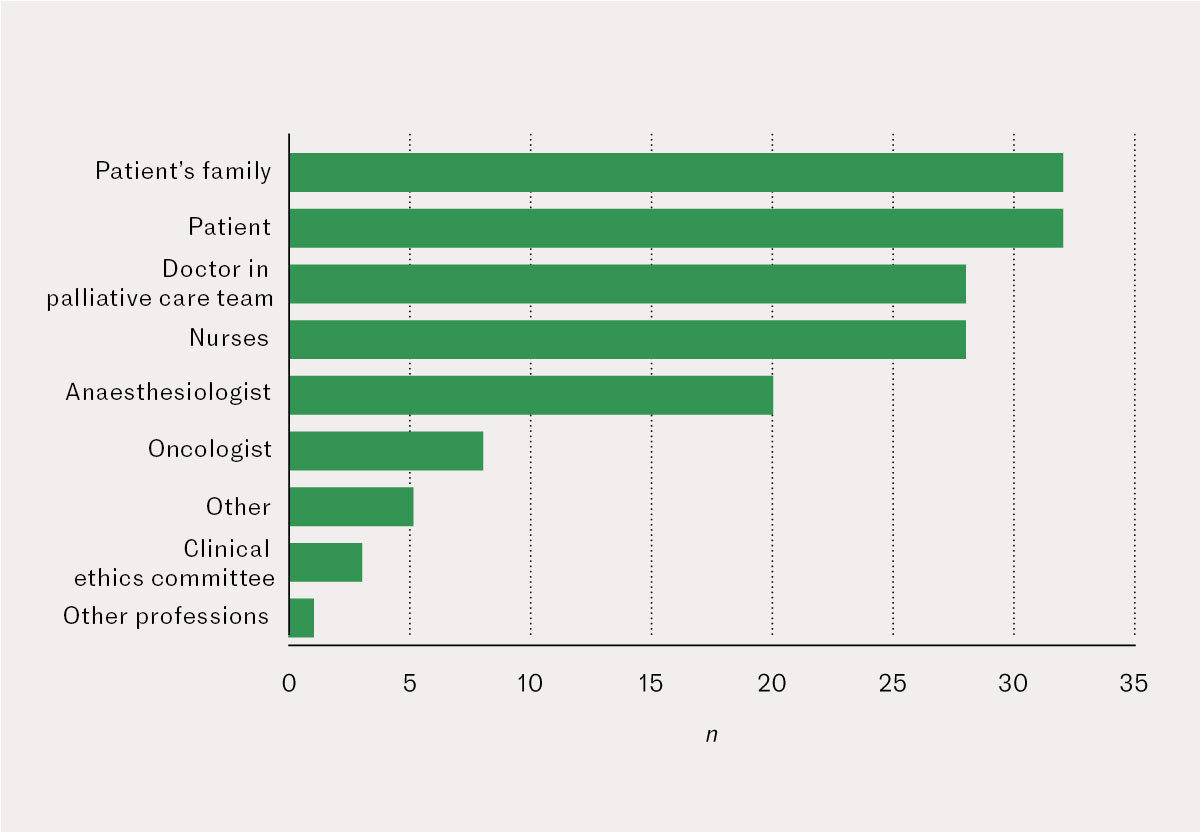

The respondents reported that a thorough, interdisciplinary decision-making process took place before the sedation was administered (Figure 2). Of the 37 who were aware that palliative sedation was practised in their department, 27 indicated that it was carried out in accordance with the Norwegian Medical Association's guidelines. Midazolam and morphine were the most common medications, and were reported by 29 and 30 respondents, respectively, while 9 also indicated the use of propofol.

The indications reported were primarily intractable dyspnoea and pain. Seven of the doctors cited psycho-existential suffering as a reason for sedation, and six specified delirium. Eighteen respondents indicated that most patients died within a few hours of palliative sedation being initiated, while 13 reported it happening a few days later. According to 26 participants, non-invasive ventilation and high-flow oxygen therapy were gradually tapered and discontinued after sedation, while one indicated this would continue until the patient died, and three discontinued it immediately after sedation. Two reported that fluids were administered, one mentioned antibiotics, and five referred to an individual approach. Otherwise, all other life-sustaining treatment was terminated, including artificial feeding.

Qualitative analysis of free-text comments

Fifty-five free-text comments from 24 of the participants elaborated on their responses.

Joint decision-making

The decision-making process varied considerably but generally took the form of extensive team discussions over time. The importance of the collaboration with nurses and the palliative care team was emphasised, as were thorough discussions with the patient and their family. A clinical ethics committee could also be consulted to explore alternative treatment options or to resolve professional disagreements. Some participants reported that the intervention was normally initiated by a pulmonologist and the palliative care team, while in some places the pulmonologist had more or less sole responsibility for the decision. Palliative sedation was only considered when all other interventions had been exhausted, for example in cases of intractable dyspnoea that could not be optimally alleviated in a conscious state with non-invasive ventilation, high-flow oxygen therapy and/or a continuous subcutaneous infusion of morphine and midazolam.

'The patient and their family are told about palliative sedation, that this is an option if the symptoms are intolerable in a conscious state. So, the procedure is initiated when the patient and their family express a wish for this, or when the doctors indicate that no further treatment is available and the patient experiences a sensation of suffocation or severe anxiety despite receiving high doses of morphine/midazolam,.' (Comment 7)

Complex distinction

The distinction between palliative sedation and euthanasia was easily blurred. Assessing whether the patient's condition was severe enough was a challenge, as was determining whether the patient and their family wanted palliative sedation and fully grasped what it entailed. They were not always ready to accept that the end was near, despite the patient suffering severe pain and dyspnoea that were difficult to alleviate adequately with standard symptom management. The doctors sometimes found that nurses on evening and night shifts lacked the competence to deal with sedation in line with the guidelines. Ensuring that all parties understood why sedation was necessary was a challenge, as was addressing disagreements about whether palliative sedation was the right choice. Nevertheless, the pulmonologists found that having a plan in place and providing sufficient symptom relief was reassuring for the patient and their family. Use of anaesthetics, such as propofol and thiopental, could also be problematic in patients with severe pain for whom other options had been unsuccessful. Administering large doses of midazolam and morphine intravenously, along with subcutaneous infusion, did not always enable the same level of control over sedation as propofol.

'There's a fine line between active and passive euthanasia; it's difficult to distinguish between them. In specific situations like this, it would be beneficial to have clearer guidelines to rely on.' (Comment 5)

The need for reassurance and support

The fact that they had carried out palliative sedation multiple times, coupled with the strong support they received from the palliative care team and anaesthesiologists, was reassuring for the doctors. They found it less complicated in cases of advanced illness and when it had been clarified with the patient and their family in candid discussions over time about difficult subjects. Some participants worked in hospitals where palliative sedation was a collaborative effort between anaesthesiologists, high dependency units and/or palliative care units. The pulmonologists trusted that those administering the sedation were well qualified, although some felt that it could have been initiated earlier. Adhering to the Norwegian Medical Association's guidelines gave them reassurance that this was the right intervention for intractable end-of-life suffering. Even though it was not easy, protocols and colleagues were both a source of reassurance:

'These are always challenging situations, even when we have robust protocols. It's reassuring to have a number of doctors involved.' (Comment 42)

The doctors could experience prognostic uncertainty in relation to the exact stage of the patient's condition due to insufficient knowledge and experience as well as the nurses' uncertainty. Uncertainty could also arise about dosing when patients became increasingly agitated during sedation. Recommendations for medication and practical implementation could be helpful, along with greater familiarity with the guidelines. There was a desire for the grey areas to be further clarified and for the guidelines to include information on different diagnostic groups and respiratory support. The doctors found it difficult to understand the definition of palliative sedation when it means different things in different contexts, and expressed that palliative sedation was not considered exceptional or unusual for patients with end stage pulmonary disease. Clarification would therefore be beneficial:

'Ensure that there is a clear link to guidelines for end-of-life care and make the distinction between symptomatic relief and palliative sedation as clear as possible.' (Comment 1)

Discussion

Although only 50 doctors responded to the survey, we believe the results are relevant to the discussion on palliative sedation in Norway. Less than half of the doctors were familiar with the guidelines designed as a support tool in this ethical minefield. This serves as a reminder of the importance of implementation efforts and ongoing ethical discussions within the medical community. Reports of palliative sedation occurring weekly indicate a lack of clarity in its definition and that it should be confined to a small number of patients and 'extreme' cases.

Application of guidelines

The responses indicate that palliative sedation is carried out in accordance with the guidelines and that the patient and their family are involved in this decision, typically just before death. This is consistent with previous studies conducted in Norway (16). Lung cancer, COPD, pulmonary fibrosis and neurological conditions such as ALS can all cause severe symptoms in the terminal stage, and national guidelines stress that patients should receive adequate symptom relief 'even where it cannot be precluded that this may accelerate death' (17). Palliative sedation is also used for COVID-19 patients with life-threatening pulmonary complications. We are not sure if under-treatment occurs due to the ethical dilemma that palliative sedation presents, and if patients are therefore suffering unnecessarily before they die. Our study shows that, in practice, existential distress is used as an indication, but it is unclear whether this can be a solitary indication or if it has to be concomitant with somatic distress. The guidelines' restrictive stance on existential distress as the sole indication stems from the intention that such distress should primarily be addressed through other interventions. It was noted that clearer guidelines would be helpful in situations where it was difficult to distinguish between palliative sedation and euthanasia and to assess whether the patient's condition was severe enough. One of the suggestions for the guidelines was to link them more closely to other relevant guidelines/guides, including the national clinical guidelines for end-of-life palliative care (18) and the Norwegian Directorate of Health's guide entitled 'Decision-making Processes in the Limitation of Life-prolonging Treatment' (17), which is currently under revision.

Ethical challenges

Nineteen of the doctors in this study had experienced ethical challenges related to palliative sedation. These challenges were associated with the distinction between palliative sedation and euthanasia, uncertainty about whether the patient was terminally ill, and disagreements among clinicians about whether it was ethical to initiate palliative sedation. This is consistent with other studies showing that decisions are based on various assessments and values, which can be particularly difficult in patients on respiratory support (19). However, patients with incurable pulmonary conditions may experience intractable end-of-life suffering, and Materstvedt et al. argue that palliative sedation is a morally good act (20). Alleviating suffering is an ethical imperative and a central argument in the growing movement to reconsider the opposition to euthanasia (21). Do the guidelines apply to the type of end-of-life sedation described by the pulmonologists? We contend that, as long as it pertains to planned sedation for intractable suffering as opposed to acute symptom relief or the adverse effects of ongoing treatment, it aligns with the Norwegian Medical Association's definition.

Strengths and weakness of the study

Although the response rate was low and the sample was not representative of pulmonologists in Norway, this study offers valuable insights into the experiences and challenges encountered in the field of pulmonology. The sample displayed considerable variation in age and covered a range of workplaces (local hospitals and university hospitals); however, far fewer specialty registrars participated than senior consultants. This may be related to the fact that more senior consultants are responsible for administering palliative sedation, and therefore made the effort to respond. The reminder sent after the autumn meeting of the Norwegian Association for Pulmonary Medicine, where Margrethe Aase Schaufel presented preliminary findings, may have meant that more respondents were aware of the guidelines when completing the questionnaire (15 out of 50 responses arrived after sending the reminder). Internal validity and consistency in questionnaire surveys can be challenging. Six participants who indicated they were unfamiliar with the Norwegian Medical Association's guidelines nonetheless stated that their department adhered to them in relation to the aspects of palliative sedation mentioned in the questionnaire. It is therefore unclear whether the guidelines were followed in their entirety in these instances.

Conclusion

The definition of palliative sedation continues to be interpreted in various ways. Ethical grey areas present challenges, but pulmonologists report feeling confident in most situations and having strong support. The study found that the guidelines are applied following thorough interdisciplinary discussions and are also used for diagnoses other than cancer. Future revisions of the existing guidelines could benefit from the inclusion of diagnosis-specific recommendations.

We would like to extend our heartfelt thanks to the informants, and to Øystein Fløtten, Ove Fondenes, Dagny Faksvåg Haugen, Nina Elisabeth Hjorth and Kristel Svalland Knudsen for their valuable input to the questionnaire.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Førde R, Materstvedt LJ, Markestad T et al. Lindrende sedering i livets sluttfase – reviderte retningslinjer. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2015; 135: 220–1. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 2.

Lovdata. Lov om straff (straffeloven) - Kapittel 25. Voldslovbrudd mv. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2005-05-20-28/KAPITTEL_2-10#KAPITTEL_2-10 Accessed 20.10.2023.

- 3.

Den Norske Legeforening. Etiske regler for leger. https://www.legeforeningen.no/om-oss/Styrende-dokumenter/legeforeningens-lover-og-andre-organisatoriske-regler/etiske-regler-for-leger/# Accessed 20.10.2023.

- 4.

Husom N. Bærum-saken endelig henlagt etter bevisets stilling. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 2002; 122: 227.

- 5.

Førde R, Aasland OG, Falkum E et al. Lindrende sedering til døende i Norge. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 2001; 121: 1085–8. [PubMed]

- 6.

Den Norske Legeforening. Retningslinjer for lindrende sedering i livets sluttfase. https://www.legeforeningen.no/contentassets/cc8a35f6afd043c195ede88a15ae2960/retningslinjer-for-lindrende-sedering-i-livets-sluttfase-2014.pdf Accessed 20.10.2023.

- 7.

ESMO Guidelines Working Group. ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of refractory symptoms at the end of life and the use of palliative sedation. Ann Oncol 2014; 25 (Suppl 3): iii143–52. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Board of the European Association for Palliative Care. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework for the use of sedation in palliative care. Palliat Med 2009; 23: 581–93. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Arantzamendi M, Belar A, Payne S et al. Clinical Aspects of Palliative Sedation in Prospective Studies. A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021; 61: 831–844.e10. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Blondeau D, Roy L, Dumont S et al. Physicians' and pharmacists' attitudes toward the use of sedation at the end of life: influence of prognosis and type of suffering. J Palliat Care 2005; 21: 238–45. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 11.

Fredheim OM, Skulberg IM, Magelssen M et al. Clinical and ethical aspects of palliative sedation with propofol-A retrospective quantitative and qualitative study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2020; 64: 1319–26. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Surges SM, Garralda E, Jaspers B et al. Review of European Guidelines on Palliative Sedation: A Foundation for the Updating of the European Association for Palliative Care Framework. J Palliat Med 2022; 25: 1721–31. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 13.

Payne SA, Hasselaar J. European Palliative Sedation Project. J Palliat Med 2020; 23: 154–5. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 14.

Surges SM, Brunsch H, Jaspers B et al. Revised European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework on palliative sedation: An international Delphi study. Palliat Med 2024; 38: 213–28. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 15.

Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: a strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand J Public Health 2012; 40: 795–805. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

Førde R, Kongsgaard U, Aasland OG. Lindrende sedering til døende. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 2006; 126: 471–4. [PubMed]

- 17.

Helsedirektoratet. Beslutningsprosesser ved begrensning av livsforlengende behandling. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/veiledere/beslutningsprosesser-ved-begrensning-av-livsforlengende-behandling/norsk-versjon Accessed 20.10.2023.

- 18.

Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonale faglige råd. Lindrende behandling i livets sluttfase. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/faglige-rad/lindrende-behandling-i-livets-sluttfase Accessed 14.8.2024.

- 19.

Guastella V, Piwko G, Greil A et al. The opinion of French pulmonologists and palliative care physicians on non-invasive ventilation during palliative sedation at end of life: a nationwide survey. BMC Palliat Care 2021; 20: 68. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 20.

Materstvedt LJ, Ottesen S, von Hofacker S et al. Unødvendig lidelse kan unngås ved livets slutt. Dagens Medisin 29.1.2019. https://www.dagensmedisin.no/debatt-og-kronikk/unodvendig-lidelse-kan-unngas-ved-livets-slutt/408954 Accessed 20.10.2023.

- 21.

Blomkvist AW, Zadig P, Schei E et al. Legeforeningen bør representere medlemmenes syn på dødshjelp. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2022; 142. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.22.0199. [PubMed][CrossRef]